Welcome to our significantly revised Aligned Course and Syllabus Design teaching resource. This landing page includes the following:

- an Introduction,

- an overview the 4As of Course Design, our overarching framework,

- an introduction to Learning-Centered Syllabus Design, and

- a selection of Deeper Dive Resources

The navigation bar at the left will link you to guidance on using this teaching resource, as well as individual course and syllabus design pages for each of the 4As.

Introduction

“Course design” refers to the process of developing course learning aims, then selecting assessments, learning experiences, and materials that will align with aims to develop a course that animate your overarching goals for student learning and enduring understanding.

In the article “Understanding by Design,” Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe first set out an evidence-based course design process encouraging faculty to shift from identifying what content to cover during a course and where to place homework and exams. Wiggins and McTighe offered a "backwards design" framework in which teachers would work to “constructively align” three elements for an aligned course design process. The three elements ask teachers to:

- identify desired results in writing learning Aims (in cognitive, affective, or psychomotor, learning realms), then

- develop appropriate, multiple means of Assessment that would engage students in demonstrating learning, and

- plan learning and teaching Activities (from homework to to individual and collaborative inclass work) to engage learners in practicing skills and gathering feedback.

Mount Holyoke’s “Learning-Centered” webpage describes backward design engaging instructors in “thinking carefully about what knowledge and skills you want students to take away at the end of the semester. From there, you reverse engineer the course.” As a course begins, then, instructors “deliver forward” by, for example, setting out a class session’s learning aims, linking these to the session’s planned teaching and learning activities (interactive lecture segments and activities, for example). A further step in delivering forward might be to link a session’s work with recent learning, and/or to future assessments.

The aligned backward design approach is neither a teacher- or student-centered approach to teaching and learning. Rather it takes a “learning-centered” approach that acknowledges learning as a common goal, and constructing knowledge, or meaning making, as requiring participatory interactions between teachers and learners, between learners and course materials, and between learners. Learning as involving invitations for, and acts of participation builds the definition of learning offered by Frank Coffield following an investigation with colleagues:

“Learning refers only to significant changes in capability, understanding, knowledge, practices, attitudes or values by individuals, groups, organisations or society. Two qualifications. It excludes the acquisition of factual information when it does not contribute to such changes; it also excludes immoral learning as when prisoners learn from other inmates in custody how to extend their repertoire of criminal activities.” (7).

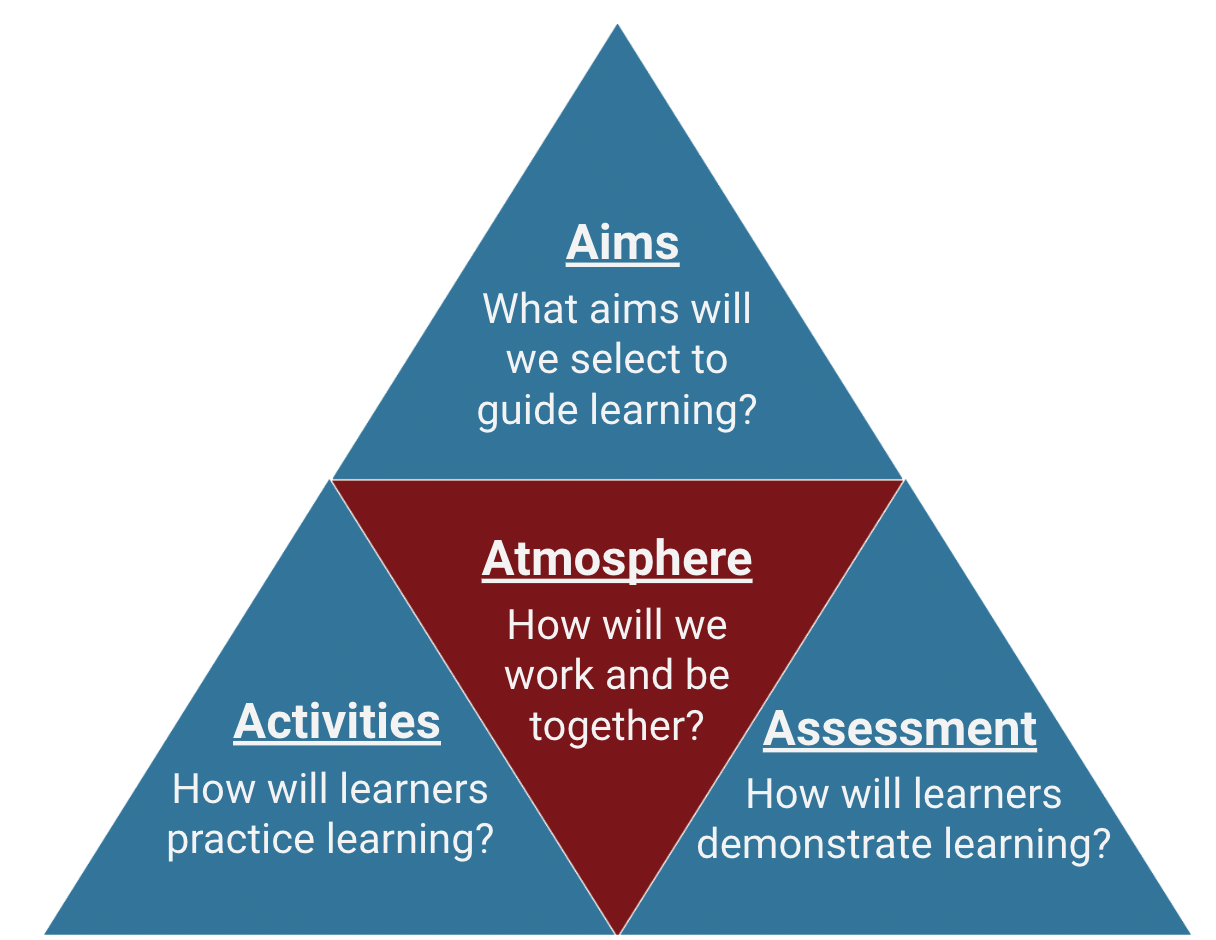

We have drawn on the three points of backward design to build a 4As Course Design Framework that structures this Aligned Course and Syllabus Design teaching resource. To the Aims, Assessments, and Activities points noted in our opening recap of Wiggins and McTighe, we add Atmosphere as a fourth element to make room for planning that is anchored to understanding learning and learners, disciplinary and learner contexts, inclusion and accessibility.

The framework we call The 4As - with Atmosphere, Aims, Activities, and Assessments components - is the foundation for this Aligned Course and Syllabus Design teaching resource.

4As Framework for Course Design

In the sections below, we introduce each A with its corresponding question to provide an overview, and incorporate links to pages devoted to a particular and its aligned Syllabus Activity.

Atmosphere - How will we be and work together?

The “we” who come to learning spaces - teachers and learners - bring expectations also about what and who matters, about how learning should or could happen, or about what roles and responsibilities the players in this learning space should or might take on. With 4As Course Design, then, we focus on creating climates for learning based on what we bring, who is gathered together, where they are in their learning processes, where they will venture as learners during, after, and beyond this course, and overarching goals that we have as teachers, disciplinary scholars, and future-looking researchers.

As instructors we can survey two domains to understand the atmospheres that provide contexts for our teaching and for student learning: 1) the university, departments, fields, and learning spaces linked to our courses, and 2) the communities, cultures, and purposes that our broad range of students bring into the classrooms we create with them.

In this, we consider the aspirational and operational norms explicitly or tacitly informing teaching and learning. In working to understand contexts and norms, we can begin to discern and describe the roles of learners and teachers, and our shared responsibilities as people who create and sustain course learning climates.

Aims - What aims will we select to guide learning?

When talking with peers about courses we teach, most instructors can identify our teaching goals - what we hope students will learn, what we plan to cover, and what we believe students should learn in our courses. Writing up these ideas as learning-centered Aims to anchor our course planning for Activities and Assessments is a more difficult task. In part it is difficult because we need to shift into writing for an audience of learners rather than of peers. With students as the main audience, we shift to writing for learners as people who are new to our courses, our fields, our core concepts, content, and practices. A second aspect of this difficulty comes from needing to devise a sequence of aims that is logical from a novice rather than an expert point of view.

Activities - How will learners practice learning?

This 4As component emphasizes the need to plan relevant learning experiences for students to practice cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills, apply course concepts through critical learning and thinking practices, and make meaning as they co-learn within networks that involve other learners: teachers, peers, community members, authors of course materials, whatever their learning space (inperson, online, in lab or field or performance or maker settings). As instructors we can create activities, including homework and inclass activities, that provide an orienting task, a starting point for learning to learn, to serve as context to prompt students to shift into learning-oriented “thinking while studying.”

Typically the course calendar and syllabus narrative are constructed to serve as an accounting of topics, tasks, readings, and due dates. However, by preparing supplemental assignment and activity documents that set out the purpose, skills, knowledge, and task requirements, you will provide for your students with a meaningful learning information, and become more aware of what you are asking students to complete, and of how you can draw on Activities to gather data about student learning in process and practice.

- Activities & Course Design webpage

- Syllabus Activity #3 - Course Schedule and Major Assign Descriptions webpage

Assessment - How will learners demonstrate learning?

Developing a course learning climate and creating course learning aims are foundations for designing Assessments that call students into demonstrating learning. All schemes for backward design, assert that Activities and Assessment components are most effectively developed in alignment with course learning Aims, and integrated into a course as companions to each other whether planning a course, a syllabus, or components of a class session. Three core questions can launch learning-centered Assessment thinking:

- What types and variety of assessment will let me know that learners have achieved the course learning aims?

- What activities, maybe offered as formative assessments, will help me learn whether - what and how - students are learning?

- How will the assessments I select align with the course learning aims, so that the work they complete to demonstrate learning feels possible and valuable to learners, and reflects the level of learning an aim specifies?

Developing Assessments and Activities to support students in practicing and demonstrating learning is an iterative process, with some course design scholars advocating for starting with Assessment planning, and others with Activities, while many instructors work with each at the same time. Whether there are key practice skills you need to incorporate into a course or specific types of assessments that need integrating, these are often key considerations guiding teachers navigating these interactions.

Learning-Centered Syllabus Design

In 2016, Michael Palmer, Lindsay B. Wheeler, and Itiya Aneece were among the first syllabus-focused researchers to ask "Does the document matter?” and follow up with a study based on metanalysis of existing research and a mixed methods experiment to gather student responses to sample traditional and learning-centered syllabuses.

The article reporting on their investigation of “the evolving role of syllabi in higher education," the authors summarize learning-centered syllabuses as “characterized by engaging, question-driven course descriptions; long-ranging, multi-faceted learning goals; clear, measurable learning objectives; robust and transparent assessment and activity descriptions; detailed course schedules; a focus on student success; and an inviting, approachable, and motivating tone” (36).

Further, based on student responses, “When students read a learning-focused syllabus, they have significantly more positive perceptions of the document itself, the course described by the syllabus, and the instructor associated with the course” (36).

To their question “does the document matter,” they conclude - as does ensuing scholarship of learning and teaching research conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, and Australasia - that the document matters, and that a syllabus “grounded in evidence-based teaching and learning principles and student motivation theories” and “crafted through a systematic course design process” (37) matters even more.

The four syllabus activities that are companions to the 4As sections of this teaching resource build on what we’ve learned - via empirical research, our own classroom experiences and students feedback, and working with instructors across disciplines, course formats, teaching experiences and ranks, identities and cultural affiliations, and time frames available for developing or redesigning a course.

- Syllabus Activity #1: Draft a Reflective Course Memo webpage

- Syllabus Activity #2 - Draft the 1st Narrative Pages webpage

- Syllabus Activity #3 - Course Schedule and Major Assign Descriptions webpage

- Syllabus Activity #4 - Finalize Your Syllabus webpage

Because instructors come to Course and Syllabus design from an array of contexts and for multiple purposes, we have created a Using this Resource page to outline six different approaches for navigating this resource.

Deeper Dive Resources

As with each of the 4As sections, we curate small sets of resources so that readers have the option of investigating research or praxis resources that extend the conversation beyond those we’ve already incorporated. This deeper dive section focuses on learning, course design, and syllabus design.

On learning and learners

- “What the Student Does: Teaching for Enhanced Learning,” John Biggs foundational open access article, illustrates a focus on what the student does through examples of how two prototypical students can benefit from attention to practice in learning.

- In the “Back to Basics” chapter (pages 5-14) of the Just Suppose Teaching and Learning Became the First Priority monograph, Frank Coffield distinguishes between learning as acquisition and as participation, offering a definition of learning in a participation mode.

- Melinda Owens and Kimberly D. Tanner’s article frames "Teaching as Brain Changing: Exploring Connections Between Neuroscience and Innovative Teaching," linking neuroscience and learning science to illustrate how “at their most fundamental and mechanistic level, teaching and learning are neurological phenomena arising from physical changes in brain cells. The duo explores various teaching techniques - frequent active homework, think-peer-share, concept maps, problem-based learning, using culturally diverse examples - and their possible neuronal bases to advance teachers’ and learners’ understandings of how learning works at nervous system and neurobiological levels.

- The Radical Copyeditor’s website approaches their work openly acknowledging that language is not neutral, that “through language we communicate values, maintain norms, and dictate what’s possible.” Words matter everywhere, and especially in learning contexts. Their resources on land acknowledgments that don’t perpetuate oppression (webpage), for writing about transgender people with care and context (webpage), and on “the power of everyday language to cause harm” (website).

On course design

- John Biggs revisits the "Constructive alignment in university teaching" that informs his consulting work across multiple decades and 5 editions of Teaching for Quality Education at University. The 2014 article sets out Biggs’ approach to backward design, and offers strategies in acknowledging that in initial course (re)design “requires time and effort in designing teaching and assessment.”

- Two views on shifting from teacher-centered to student-centered to learning-centered course design:

- Ian Roth’s blogpost serves as a general overview of each of these approaches.

- Doris Santoro Gómez more fully explores the metaphor of “moving from margin-center,” which she asserts translates poorly to student-centered pedagogy. A google document summary that links to her full article, notes Gómez’s primary concern that the use of a margin-center schema polarizes, even freezes, student teacher relationships by implying that those “with authority” always have power. For example, in student-centered pedagogies, students are always at the center and teachers are always “in the margins” as facilitators. To counter the polarizing of roles, Gómez addresses learning-centered pedagogies to create a continuum between margin and center and that differentiates between a teacher’s roles of “being an authority” and “being in authority.”

- In the “Integrated Course Design” IDEA paper L. Dee Fink frames his approach to backward design, offering a model, a learning taxonomy, strategies for active learning, and criteria for establishing forward-looking assessments.

- Learning-centered design infuses principles and practices related to accessibility, inclusion, belonging, and wellbeing rather than adding them in based on formal accommodation processes. Five resources can serve as a grounding for beginning infusion work:

- “Teaching with Access and Inclusion: Concepts, Principles, Practices” - google document

- “Course Design” page from the UDL on Campus website

- “Support Belonging in the Classroom,” a UIowa teaching resource pdf that faculty can draw on in working through their own school’s data reporting on students’ sense of belonging on campus

- The Provost’s Council on Student Mental Health at University of Minnesota “Build your syllabus to promote student wellbeing” google document blends specific course and class planning suggestions with an appendix of further resources.

- “Start with the 7 Core Skills” as a webpage notes the why and how of creating accessible course materials through accessibility-informed practices for creating hyperlinks, lists, and tables, and for providing alternative text, creating captions, descriptions and transcripts for multimedia platforms, and accessible use of color as part of visual communication.

On syllabus design

- William Germano, and Kit Nicholls discuss ideas from Syllabus: The Remarkable, Unremarkable Document that Changes Everything in their Dead Ideas in Teaching and Learning podcast with transcript, focusing on everyday questions about the syllabus, and discussing why and how rethinking the syllabus can let the document become a starting point for addressing “larger dead ideas about teaching, learning, and student engagement.”

- “Finalizing Your Learning-Centered Accessible Syllabus.” This 90-minute August 2023 Accessibility Ambassadors webinar is available as a video with presentation slides. The session links learning-centered course design strategies to specific rhetorical, pedagogical, and accessibility practices for developing a course syllabus for its primary audience: learners. The facilitators are a teaching-learning consultant who teaches first year and graduate-level courses drawing on the 4As’ inclusive, accessible, learning-centered principles and practices, and an academic technologist whose focuses include creating inclusive accessible digital course materials.

- The Princeton University “What is the Purpose of a Syllabus?” webpage notes presents the syllabus as a document that “may – and should – serve multiple purposes: it not only provides a schedule of the semester’s activities and assignments but also invites students into the work of learning,” and encourages faculty to draw on “several - or all” ot the different ways they list in thinking about rhetorical framing of a syllabus document.