Building on Atmosphere’s focus on creating learning spaces where teachers and learners will be and work together, this Aims section opens with a reminder that learners remain our main audiences in drafting and selecting Aims for each of our courses. Clearly written, meaningful course-level Aims communicate our expectations about the type and depth of knowledge and range and accuracy of skills learners will need to practice as they engage Activities to practice learning, and as they complete Assessments to demonstrate learning.

Introduction

We’ve selected “Aims” to bridge the varied vocabulary of goals, objectives, outcomes that teachers and scholars use to name this significant course design starting point. “Aims” also nicely serves as a mnemonic for remembering and aligning the 4As course design framework.

And, typically, we will reference “learners” more often than “students” to name the general group of people who enroll in our courses and serve as our primary audiences. This shift acknowledges that learning work - specific skills and processes, roles and responsibilities - is required in higher education courses. Frank Coffield describes this as a shift from passive and sometimes performative acquisition of knowledge or information toward collaborative and often learning-motivated participation in learning that provokes “significant changes in capabilities, understanding, knowledge, practices, attitudes or value by individuals, groups, organizations or society” (“Just Support Teaching and Learning Became the First Priority” as pdf).

Learning Aims

When talking with peers about teaching, we often identify our teaching goals - our hopes about students' learning, intentions for course focuses, beliefs about what's most important for students to show that they "know" about the course topic, and established traditions for types of assessments to be completed. Translating these big picture teaching goals into actionable student learning aims is a more difficult task, and one that can be helped by thinking about the shift as akin to the metaphor of moving between the balcony (where we often sit as teachers) to the dance floor (where learners move about) in order to observe how individual dancers actually use the dance moves they've been taught, and to make sense of the - sometimes beautiful, sometimes not yet fluent - movement variations they create.

The key roadblock for many moving from the balcony to the dance floor? That would be shifting from writing course materials in order to communicate within an audience of academic peers, or to an audience of ideal students, to approaching the composing of Aims for the broad groups of learners actually in our courses who will be our primary audiences. Does this mean we stop considering peers as an audience for our course-related work? Of course not. We continue seeking balcony-level feedback in conversations with peers about that dance floor and the choices we are making. In this way, peers join us in shaping ideas and opportunities for learning about and on the dance floor of our courses.

Another key benefit for moving toward writing learning-centered Aims? Having spent time on the dance floor with learners as a primary audience for these Aims, and talking with peers as we build courses we’ve gathered data through observation and reflection to expand our practices so that our smartly written aims help us to select course topics and curate relevant content, focus class session plans, share purposes for core course activities, and shape major assignments and assessments that are meaningfully aligned with those Aims. These are acts of engaging in backward course design.

Learning Taxonomies

In designing a course and composing a syllabus as the audience-facing document representing a course, teachers often initially draw on general learning taxonomies that set out an iterative set of learning or cognitive aims to categorize capacities required for completion of courses, and on campus-specific core student learning outcomes that represent learning benchmarks to be met for graduation. Links to each campus’ core requirements are included in “Writing Aims Linked to Learning and Development Outcomes,” available as a google document, which offers suggestions for weaving these into course aims.

“Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy and Fink’s Significant Learning Taxonomy,” set out in a pdf, brings together the two frameworks most common taxonomies called on in higher education. Though differently named and organized, each offers course designers three broad categories for developing Aims:

- Learning or cognitive aims might include remembering, understanding, and applying foundational knowledge; and integrating content and concepts through integration that leads to analysis and evaluation;

- Developmental or affective aims that “includes the manner in which we deal with things emotionally, such as feelings, values, appreciation, enthusiasms, motivations, and attitudes” (“Bloom’s 3 Taxonomies,” as a pdf); elements here include human dimensions ranging from interpersonal relationships within course and community teams, to course and civic leadership, to caring about learning as an individual and in relation to accessibility and inclusion, and to learning how to learn in factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive dimensions); and

- Psychomotor aims or physical action skills in realms of physical movement, coordination, adaptation, performance and decision-making in disciplines as varied as arts and kinesiology performance spaces, science and language labs, and health and counseling interactions.

The resources that follow focus on writing learning-centered aims, reflective questions for reviewing aims, and essays by teachers reflecting on their course design experiences.

Resources for writing learning-centered aims

- The google folder “Bloom and Fink on Writing Aims” includes practical resources for brainstorming, sketching out, wording, and sequencing learning aims.

- Also, the “Examples of Aims” google slidedeck brings together examples from 15 courses, which offer structures and wordings that can be drawn on across learning space and disciplines.

Aims reflection questions

The questions noted below, are meant to prompt further reflection about learners and learning during the (re)drafting of course learning aims as statements of what students will know or do by the end of your course:

- Do the verbs I’ve selected clearly indicate the knowledge and/or skills I want students to practice and demonstrate as they work to achieve the individual and collective aims?

- Are my aims measurable? Take time to notice where you may have used understand or appreciate, for example, as the main verbs in an aims statement, then determine what more specific verbs you could replace these generic verbs in order to (a) convey the level, depths, or types of learning that I have in mind, and (b) set the parameters for how I will measure, or assess, learning.

- In addition to cognitive learning aims, do I specifically incorporate aims linked to affective learning and/or for psychomotor learning that are also substantially part of course learning and assessments?

- Are these course aims written so that students can meet essential course Aims in ways that are accessible and inclusive? Drawing on prevailing definitions of essential, the UMTC Disability Resource Center webpage offers this analysis: “You may think about essential requirements as ‘the what’ that students need to demonstrate they are learning. Flexibility or variation with ‘the how,’ or the way that students demonstrate their competencies, … allows instructors to maintain the integrity of essential course requirements and allows students to show competency, knowledge, and skill rather than being assessed on their ability to demonstrate knowledge in a singular way.”

- Where outside agencies or accreditation-related requirements impact course learning aims, how will I factor in aims related to those criteria?

- Are some of the aims I’m considering more appropriate linked to learning activities including homework and inclass or online activities? To major assignments or assessments? Where do I include these if not in the opening pages of a syllabus?

Essays by teachers in the syllabus revision process

- Bryan Dewsbury, in the "Deep teaching in a college STEM classroom" article, writes of personal and pedagogical experiences that “led to a reimagining of my entire pedagogical approach with a more careful consideration of whom I was teaching,” which meant that “I first needed to understand my own intersectional identity, and more deeply know who the students were as people, before thinking about ways to redevelop my curriculum.”

- John Powers outlines their process for “Converting Class Syllabi to the Outcomes Based Teaching and Learning Format” in a 2008 conference paper drawing on the aligned course design developed by John Biggs and Catherine Tang. The article is an open educational resource that will be downloaded as a PDF.

- “Constructing a Learner-Centered Syllabus: One Professor’s Journey,” an initial scholarship of teaching article by Aaron Richmond, showcases the author’s initial learning about, reflection on, and drafting of Atmosphere and Aims segments (and more) of a learner-centered syllabus.

The taxonomy resources, reflective questions and essays included in this section can work as a further springboard for the thinking you begin in drafting the Reflective Course Memo outlined in the “Syllabus Activity #1” webpage.

A Framework for Categorizing Aims

It’s common to wonder two things while designing a course and drafting a syllabus: Whether we have “enough” aims, and whether the drafted aims might actually be linked more closely to inclass or online or preparing for class activities, or to major assignment or assessment aims. We’ll come back to the “are these enough aims?” query during the Assessment and Closing sections of this teaching resource. For now, it’s that second query we’ll address: is this an overarching course aim, an aim more closely linked to guiding purposes for a major assignment or assessment, or an aim that might help me align the purposes and roles of homework in course learning?

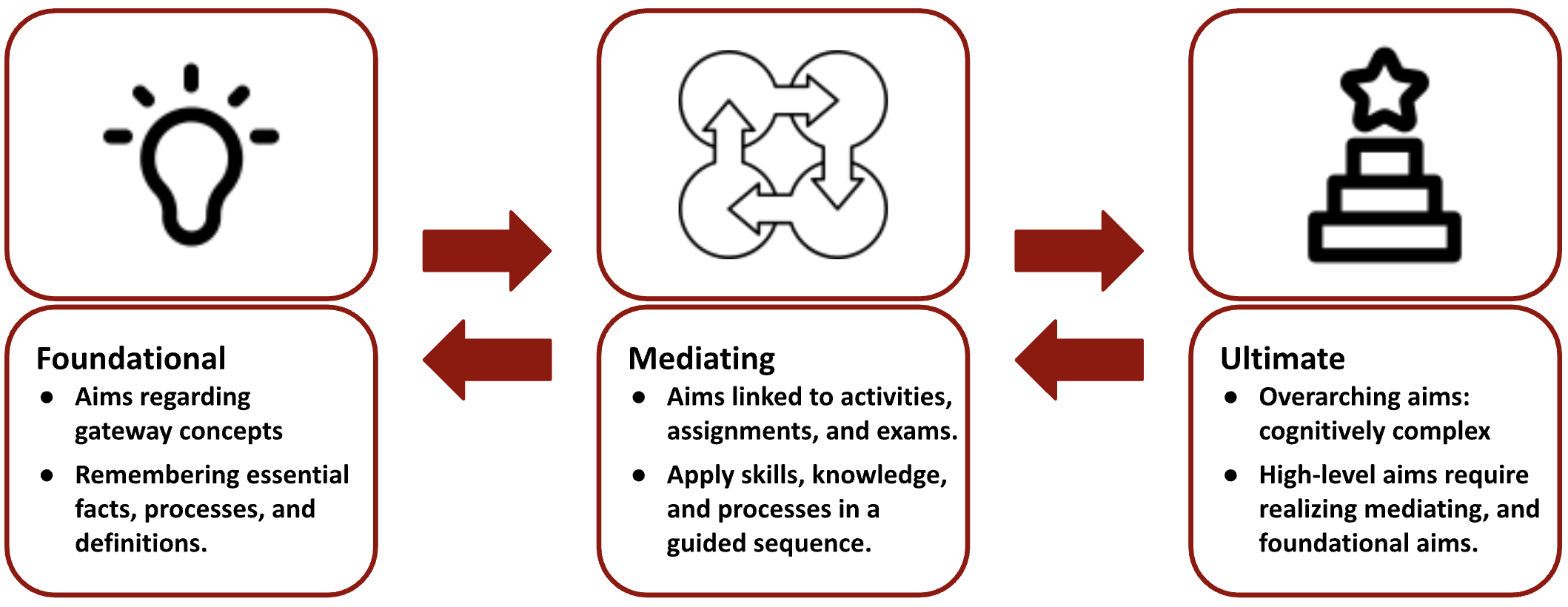

Linda Nilson’s framework Aims into three “buckets” that we share here with the naming and abridged descriptions for each of three categories: Foundational, Mediating, and Ultimate Aims.

Course Learning Aims

- Foundational Aims are related to verbs associated with remembering, understanding, and practical thinking related to threshold or core concepts and gateway skills. These aims focus on retrieving and applying essential facts, processes, and definitions as part of preparing for course work and engagement with peers in formative activities and assessments within interactive class sessions.

- Mediating Aims are linked to moderately complex individual and small group activities, as well as to a sequence of quizzes or exams, and generative stages of sequenced major assignments (eg, stages of developing projects, presentations, performances, experiments). In shaping and stating these “mid-level” aims, we begin naming criteria we and students will draw on for assessing the drafted and completed work.

- Ultimate Aims specify the course-level cognitive, affective, and psychomotor components of learning that students will need to meet to demonstrate that they have achieved benchmarked or high levels of learning in a specific course. Meeting these aims requires students to engage and go beyond the mediating and foundational aims.

Nilson offers a deeper discussion of these three buckets and an Outcomes/Aims Map example, in “Course Learning Aims - an excerpt,” a google document.

Syllabus Activity #2: Draft First Pages

This second syllabus activity is an opportunity to draw on both the Reflective Course Memo from the Atmosphere section and the narrative plus resources you’ve reviewed in this Aims section. The “Syllabus Activity #2” webpage offers strategies for drafting or revising the first 2-3 pages of your learning-centered syllabus.

Deeper Dive Resources

Authors of resources for the two segments of this Deeper Dive propose ways to deepen our focuses on the broad range of learners who are in our primary audiences, and to the frequently difficult work of curating - paring, cutting, and authentically updating - course content to be in alignment with Aims and Assessments.

Address students as primary audience

- For thinking about ways our language might generally impact our students’ first impressions of the course, and of us, attend to all “Ten Reasons Why Your Syllabus Might Suck” that The Visual Communications Guy sets out in his blogpost.

- To incorporate pronouns as a practice for speaking with students individually and collectively, the “Incorporating Names & Pronouns Into Your Courses” google document outlines key points and resources for first and continuing steps.

- “Disability Language and Identities Person-First and Identity-First Language” a section of the Pressbook Forward with Flexibility OER

- The Radical Copy Editor regularly posts and updates praxis-oriented essays addressing the power of language, sometimes the power of specific language use. As a starting point, consider pairing the “Conscious Communication and the Power of Language” blogpost with “The Power of Everyday Language to Cause Harm” blogpost.

Curate course content to align with aims

The 4As backward design framework supports moving away from “content coverage” models of sequencing courses, especially weekly schedules and course assessments. As the authors of “The Tyranny of Content: ‘Content Coverage’ as a Barrier to Evidence-Based Teaching Approaches and Ways to Overcome It” (Petersen, et al) note: “Instructors have inherited a model for conscientious instruction that suggests they must cover all the material outlined in their syllabus, and yet this model frequently diverts time away from allowing students to engage meaningfully with the content during class.”

For moving to a learning-centered teaching approach, the authors propose - and we echo in this teaching resource - three evidence-based strategies to support re-design: 1) identify the Aims, the core concepts and competencies for your course; 2) create an organizing framework for Assessments that will complete to demonstrate that they have met those core concepts and competencies; and 3) select practice Activities that work to teach students how to learn in your discipline.

A fourth part of this process, curating course content to align with course learning aims, which is a process that threads throughout the course and syllabus design process. Moving from content coverage is a process of selecting resource materials that support students’ in practicing learning (Activities) and that will support their preparation for demonstrating their learning (Assessment). The following resources will support teachers curating resources:

- The “Choosing content to achieve overarching goals” webpage offered by the Science Education Resource Center (SERC) is linked to curating or filtering content early in the course design process. The suggestions are applicable across disciplines.

- “Course Content - Auditing and Diversifying Your Content,” a webpage within CEI’s Inclusive Teaching resource, will provoke further thinking about auditing and diversifying course content.

- To specifically address content coverage in the sciences, a group pedagogical innovators, led by Christina Petersen published the article "The tyranny of content” to address “content coverage” as a barrier to evidence-based teaching, and address three strategies that instructors can adopt in moving to backward design as set out in the 4As framework of this teaching resource: 1) identify the core concepts and competencies for your course; 2) create an organizing framework for the core concepts and competencies; and 3) teach students how to learn in your discipline.