Advantages of multiple-choice exams and quizzes

- Can be used to assess a broad range of content in a brief period of time.

- Can be scored quickly.

- Skillfully written items can measure higher order cognitive skills.

Challenges of multiple-choice exams and quizzes

- Challenging and time consuming to write good items especially to assess higher order cognitive skills.

- Some correct answers can be guesses.

- Timed exams in general add stress unrelated to student’s mastery of the material.

Creating multiple choice exams

Decades of research on multiple choice exam questions has revealed important guidelines to follow to ensure student performance on your assessments accurately represents their level of understanding of the material.

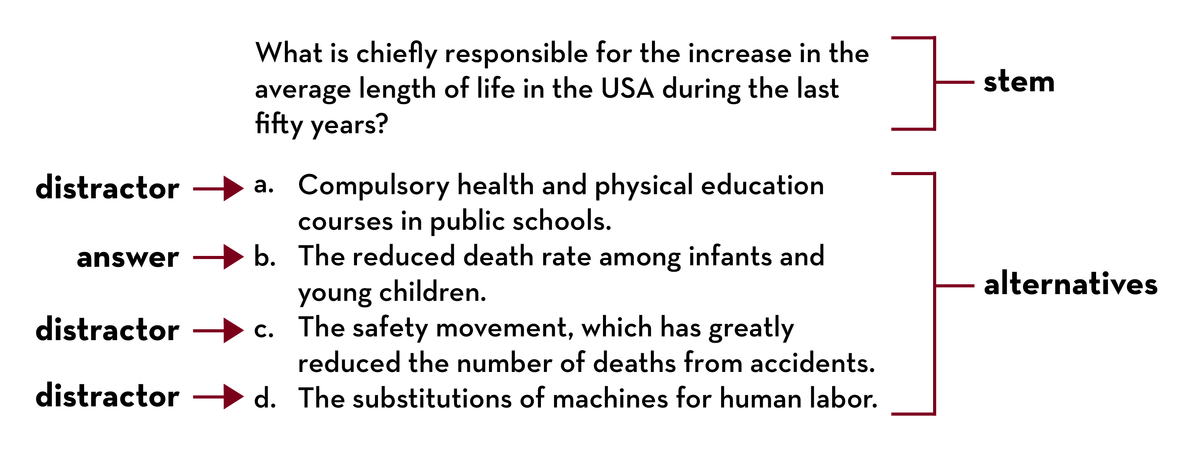

- Make all distractors plausible. Distractors are the incorrect choices available to students. Ensure that they are all plausible so that correct choice represent a student’s deeper understanding rather than rote memorization. Avoid obviously wrong or humorous options.

- Base distractors on common student misunderstandings. Create questions that require students to differentiate between the correct concept and a common misconception. You can generate and collect these misconceptions from previous assignments and activities that ask students open-ended questions.

- Ask questions at the appropriate cognitive level based on your learning aims. If the learning aims for your course are higher order e.g., analysis or application, then exam questions should address those same cognitive levels, rather than simply addressing students’ knowledge of facts.

- Reduce extraneous cognitive load of the questions. Extraneous cognitive load refers to any aspect of the question that taxes working memory but is not related to the level of understanding a student has of the topic. Extraneous cognitive load can negatively affect student performance. Ask yourself: does poor performance truly reflect a lack of understanding? Or were students cognitively overloaded with structural components of the assessment that were unrelated to content knowledge?

- Check spelling and grammar and typos. This is one of the most common complaints we hear from students about their exams.

- Ensure your options are in grammatically parallel construction.

- Avoid multiple/multiple choices.

- Limit the use of negatives - and if you do use a negative highlight the word so that it stands out.

- Reduce chances of guessing the correct answer. Sometimes the way questions are constructed give clues to the correct answer.

- Avoid the use of ‘all of the above’ or ‘none of the above’ when possible.

- Ensure that you do not give away the answer to one question in another question.

- Keep the length and complexity of alternatives similar.

Following these guidelines when writing multiple choice questions can be challenging. Using 3 alternatives is an evidence-based approach that can make this easier:

- Use 3 alternatives for your questions - 1 correct, 2 incorrect. Research shows that using 3 alternatives is optimal (Rodriguez, 2005). Writing three alternatives rather than four or more, takes less time for the instructor to come up with plausible distractors. It also takes less time for students to read the questions and take the exam, thus allowing the instructor to include more questions.

Preparing students for multiple choice exams

Ask students sample questions throughout the term and provide them with feedback on their answers. This can be done by:

- Asking a multiple-choice question during a class session using polling or student response systems and then explaining why the correct response was correct and the incorrect responses were not correct. To incentivize student participation, these formative questions could be for a small number of points. If teaching asynchronously, these questions and subsequent explanations could be an assignment or embedded into recorded lectures.

- Creating a practice exam or bank of practice questions like the type you will include on your exams. Provide students with an explanation of the answers when they have finished.

- Providing a list of learning aims that can serve as a checklist for student preparation for the exam.

Administering and grading multiple choice exams

Administering multiple choice exams

- Allow adequate time for students to take the exam. One strategy: Time yourself taking the exam as a student would, including reading the questions completely. Multiply the time by 3 – 4 to determine the time for students to take it.

Grading multiple choice exams

- Provide students with an answer key as soon as possible after they finish the exam. This provides students with feedback on their performance while it is still fresh in their memory. If the exam is online, it can be set-up to automatically provide students with the answers after they submit or at a predetermined time.

Resource document: How to prepare better multiple-choice test items (Burton et al., Brigham Young University Testing Services)

References

- For more information on creating multiple-choice exams see: Piontek, M.E. (2008). Best Practices for Designing and Grading Exams, CRLT Occasional Paper # 24.

- Rodriguez, M.C., (2005). Three Options are Optimal for Multiple-Choice Items: A Meta-Analysis of 80 Years of Research, Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 24(2), 3 – 13.