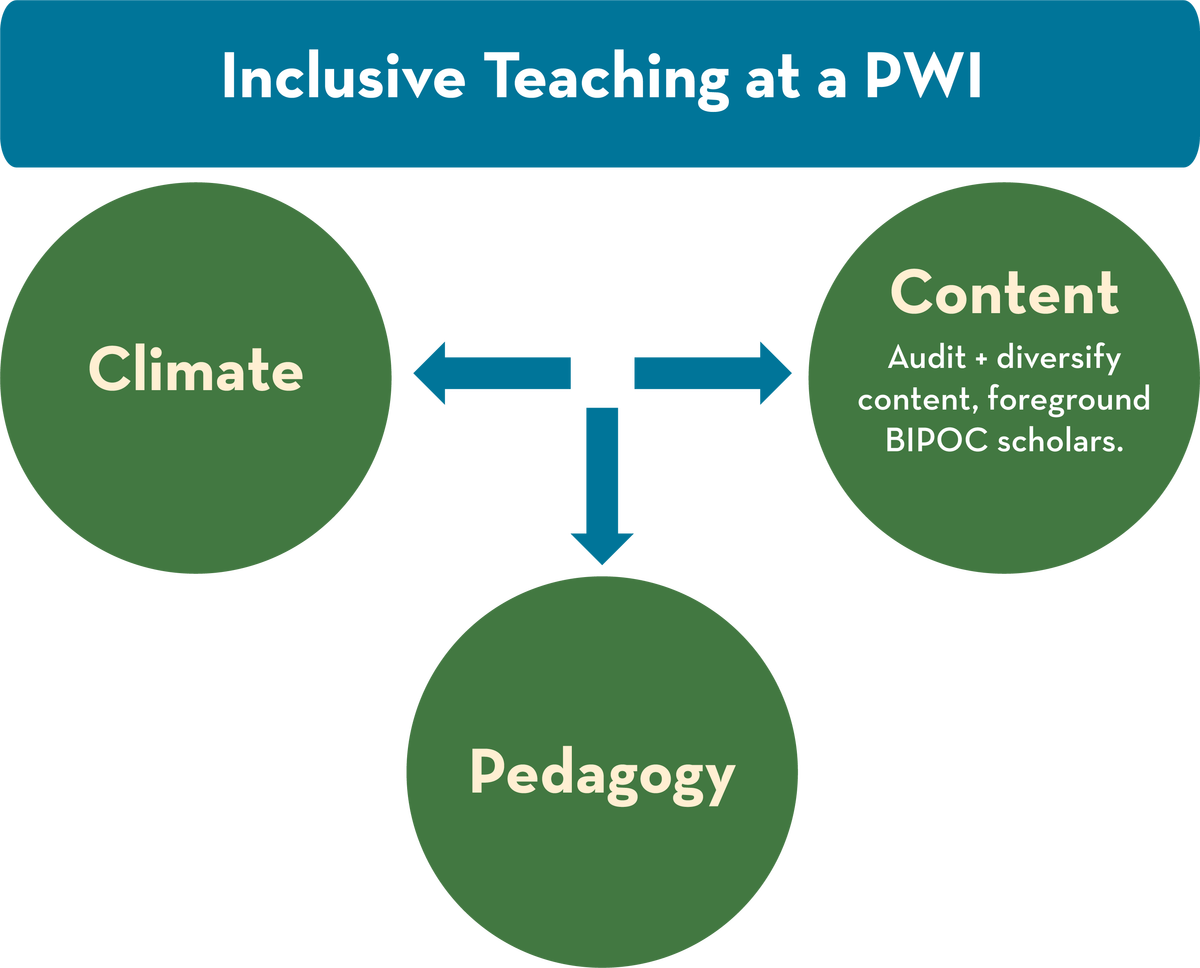

Definitions of Course Content

In defining pedagogy earlier, we also defined course content as the “clay” or raw material that students work with in order to learn. We shared Kind and Chan’s (2019) concept that an instructor’s Content Knowledge (CK) is their expertise in their subject matter including facts, concepts, theories, and typically their ongoing research in their disciplines. Students, especially novice learners and possibly first-generation college students, often have a working definition of learning as “acquiring knowledge” (course content), where knowledge is the memorization of facts and concepts as well as the replication of problem-solving as demonstrated by the instructor. These efforts are in the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, and instructors are often disappointed to see that students are not thinking critically or creatively (the upper levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy). Finally, course content is typically the parameters of the subject matter set out in the syllabus: U.S. History from WWII to the Present, Beginning Calculus, or Principles of Hydrodynamics.

Key Idea for Course Content

Audit and diversify your course content, and embed the research and creative work of BIPOC scholars in their voices. Two points are important here. First, course content is more than the textbook, readings, and other resources that instructors typically ask their students to review as homework. Second, many academic disciplines are built from Eurocentric and North American (the Global North) traditions that, in turn, are the foundations of PWIs. The canon of many academic fields is not necessarily the best of all scholarship in the discipline, but rather the best of scholarship from European and North American scholars as determined by European and North American scholars. This is not to say that our current disciplines are not excellent, but rather that they could be truly exemplary if they were expanded and diversified with the work and the voices of BIPOC scholars and creators.

PWI Assumptions for Course Content

We find there are two primary PWI assumptions about course content, and both derive from the PWI values of objectivity and universal truths. By objective, we mean something that is without bias. By universal, we mean something that is always true. The first common PWI assumption is that scientific knowledge is objective and universal, so there is nothing to diversify or make inclusive. Scientific knowledge may (at times) be universal, but it is unlikely to be objective. So while it’s true that the quadratic equation solves for the unknown X and the principles of aerodynamics govern flight, we owe our students a more expansive education that reveals the origins of scientific knowledge, acknowledges the contributions and other traditions of BIPOC scholars (including those whose insights have been appropriated), and that questions the misuses that resulted from claims to objectivity.

The second common PWI assumption is that the instructor is objective, so their identity does not (or should not) matter in the teaching of their content (scientific or otherwise). Instructors of any identity are not without bias. There are common implicit biases in teaching (read problematic assumptions) that any instructor of any identity in any field may enact. Moreover, the claims of instructor objectivity is one mechanism supporting the PWI practice of “colorblindness,” which undermines inclusive teaching at a PWI. For example, Tichavakunda (2022) considers the role of instructor bias in claims of academic misconduct. It is more truthful for instructors to claim a particular expertise and name its boundaries for their students, rather than to claim objectivity. And if instructors teach their students to be objective (rather than have particular knowledges and expertises), instructors inculcate their students to reproduce the PWI dynamics rather than change them.

Disciplines as Knowledge Systems, a Core Concept

We suggest instructors think of their disciplines as knowledge systems, where each system has its object of study, methodologies, concepts, theories, and findings or creations. We also invite instructors to think about the origins and assumptions of their knowledge systems as the things that are “taken for granted” may support PWI systems and are worth interrogating. Moreover, instructors can introduce the roles of specific people into their knowledge system. Who represents the discipline? Who are the actors, agents, or players? Who is left out? Who benefits from this knowledge system? Who is harmed? Students need to see knowledge not as a fixed category that they memorize or master, but as something created by people that evolves over time and serves a purpose. Ultimately students are the future creators of knowledge. Additionally, reframing disciplines as knowledge systems allows for a more inclusive vision, where instructors and students can conceive of multiple knowledge systems in a dynamic relationship, rather than a hierarchy of knowledge.

Suggested Practices for Auditing and Diversifying Course Content

Auditing and Diversifying the First and Second Levels

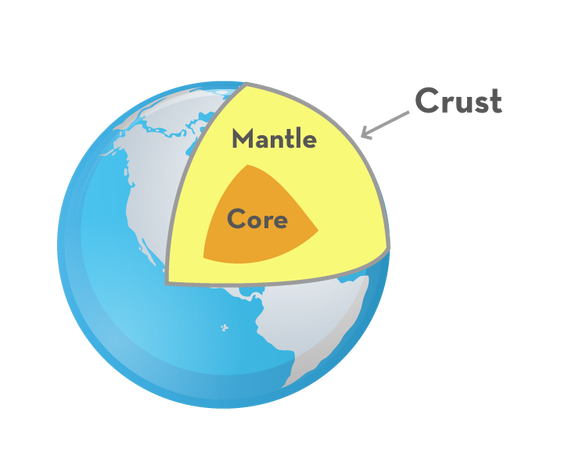

We are fond of the metaphor of the Earth’s structure when we think about course content. We imagine 3 levels of course content, moving from the outer surface level (the crust) to the middle level (the mantle) to the deepest level (the core). We suggest that instructors audit (take inventory of) each level of course content. The goal is to know what’s there and to consider appropriate ways to diversify that content.

Thinking about the first level (with some overlap with the second level), we suggest the following teaching practices:

- Draw upon a variety of types of sources for your content. Your course content will be more accessible and perhaps more engaging if you include print, visual, audio with transcripts, and other media in addition to traditional textbooks or articles. Check your materials for digital accessibility.

- Use a combination of abstract and concrete learning materials. Linking concrete examples (or even metaphors and analogies) to abstract concepts, principles, and theories improves student learning.

- Cite and use research from BIPOC and other diverse scholars in your field or discipline. This may involve working with your colleagues to systematically diversify your teaching materials, and following scholars in your field who already do this work.

- Diversify your representations, but do not tokenize. Are slides and images representative of diverse issues, themes, and communities, but not merely symbolic or tokenizing? Do data sets, case studies, and other learning materials include meaningful representations of diverse issues, themes and communities?

Thinking about the second level, we suggest the following teaching practices:

- Bring diversity to central issues or themes in your course. Embed these themes rather than add them as a sidebar or separate unit. The point is to put diverse themes in relationship with the PWI themes that may be the “default” for your course content.

- When possible, provide options for major assignments, so students may choose one that best aligns with their goals. We discussed in the Pedagogy Section the importance of varying assignments and providing options for pedagogical reasons. It’s also important to encourage students to work with content (for major assignments and projects) that is relevant and meaningful to them. So, when possible, provide options for topics, themes, and other content.

- If feasible, use multiple modes of delivery for course content. Design a user-friendly course site that provides one home base for the course. Whether you teach in-person or synchronously online, provide slides or outlines of class sessions. Consider creating brief recordings or tutorials for challenging content or misconceptions as supplemental learning materials.

- Rethink the course policies in your syllabus for PWI “defaults.” Instructors all inherit policies on attendance, participation, late assignments, exams and other course mechanics. Many of these policies create barriers to learning.

- Consider the identities and positionalities of your students when designing in-class learning activities (or asynchronous group activities). Throughout this guide and in the Climate Section we have proposed alternatives to PWI practices that acknowledge rather than ignore racial and Indigenous dynamics.

Considerations for the Third Level

Our third level of course content may surprise instructors, and we understand some instructors may question whether these dimensions comprise course content at all. We argue that they do encompass course content, but in ways that are closer to the foundations of a PWI as a system. This third level of course content also invokes our earlier core concepts, PWI assumptions, and suggested teaching practices on climate and pedagogy.

Teaching “styles” are the ways instructors are oriented to their students and how instructors envision and enact their relationship with them. There are many different approaches to teaching, and one’s teaching “style” might even vary depending upon the discipline, course and level (first-year courses, graduate courses, etc.). Pratt and Collin’s Teaching Perspectives Inventory is one model that prompts instructors to reflect on their beliefs, intentions, and actions. It’s not that there is a “correct” or more “inclusive” teaching style, but rather that instructors should consider the personal and social dimensions of teaching. And perhaps consider other possibilities for how they relate to their students.

Interpersonal dynamics are often discussed in terms of students - their identities, positionalities, majority or minority status. But the identity and positionality of instructors is an important dimension of course content. Various PWI assumptions would suggest otherwise as “colorblindness” and “objectivity” press towards the fiction that white instructor identity doesn’t matter as long as they are well prepared and credentialed. Furthermore, BIPOC instructors face differential consequences for implementing inclusive teaching practices than white instructors do (Pittman and Tobin 2022). Instructors should be aware of, and be strategic about, the ways that their identities affect how they teach.

Power dynamics intertwine with instructor/student identities and interpersonal dynamics. In the PWI context, there are 3 common “problems” that arise related to power dynamics. These problems are teaching practices or student responses that are attempting to be inclusive of BIPOC perspectives but instead reinscribe the marginalization of BIPOC students.

- The problem of “talking about” (teaching about) “other people’s people.”

- The problem of tokenizing (symbolically including) BIPOC students, instructors, staff and their experiences, scholarship, and creation.

- The problem of “trauma porn” - the reduction of BIPOC experiences, histories, and communities to their trauma, tragedies, and marginalization.

We suggest 3 alternatives to these “problems:”

- Instead of teaching about “other people’s people,” locate the voices of BIPOC scholars and creators and let their voices lead the learning. Foreground the work of BIPOC scholars and creators (Williams and Peifer 2022).

- Instead of tokenizing, center and embed the scholarship of BIPOC scholars/creators in a meaningful way.

- Instead of emotional, traumatic content on BIPOC communities and lives, present a 360 degree picture using the work of BIPOC scholars.

Ways of knowing is similar in meaning to the term epistemology. Indigenous ways of knowing challenge the human-centric bias of Western knowledge construction that puts human needs/wants above the stewardship of the Earth; the focus on short term outcomes versus a longer view of time and human effects; and the Western tendency to classify, categorize, and rank versus a holistic view of all that encompasses life (Smith et al. 2019). There are other ways of knowing that are not Indigenous, but Indigenous ways of knowing have become more recognized at PWIs both for its contributions to science education but also for its role in decolonizing higher education. We invite instructors to learn about diverse ways of knowing in their disciplines by finding and following scholars doing this work.

This third level of course content is circuitous. But it is also the level where profound change can happen. We believe that working with our disciplines as knowledge systems and the related explorations of teaching styles, interpersonal dynamics, power dynamics, and ways of knowing will help undo PWI teaching practices that are exclusionary.

Course Content References

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies. 14 (3): 575-599.

Pittman, Chavella and Thomas J. Tobin. Feb 7, 2022. “Academe Has a Lot to Learn About How Inclusive Teaching Affects Instructors.” The Chronicle of Higher Education.

https://www.chronicle.com/article/academe-has-a-lot-to-learn-about-how-inclusive-teaching-affects-instructors

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai, Tuck Eve, and K. Wayne Yang, eds. 2019. Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. New York: Routledge.

Tichavakunda, Antar. Jun 30, 2022. “Let’s Talk About Race and Academic Integrity.” Inside Higher Education.

https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2022/06/30/academic-integrity-issues-are-not-race-neutral-opinion

Williams, Jennie and Janelle Peifer. Jun 7, 2022. “White Scholars, Black Spaces.” Diverse Issues in Higher Education. https://www.diverseeducation.com/opinion/article/15292841/white-scholars-black-spaces